The tooth the whole tooth and nothing but the tooth; Shark tooth study finds startling information on great white sharks

17th August 2017 | by Georgia FrenchScience alert! Read Founder and Chairperson Georgia's new discovery about great white sharks

The most famous part of a great white shark is probably its teeth, and these were one of the first things that biologists studied about them. For decades a certain belief about their tooth shape has been unilaterally accepted, and quoted countless times in books and scientific papers as a basic fact of white shark biology. I’m excited to say that my research, just published as an early view article by the Journal of Fish Biology, blows this paradigm wide open.

What was thought to happen:

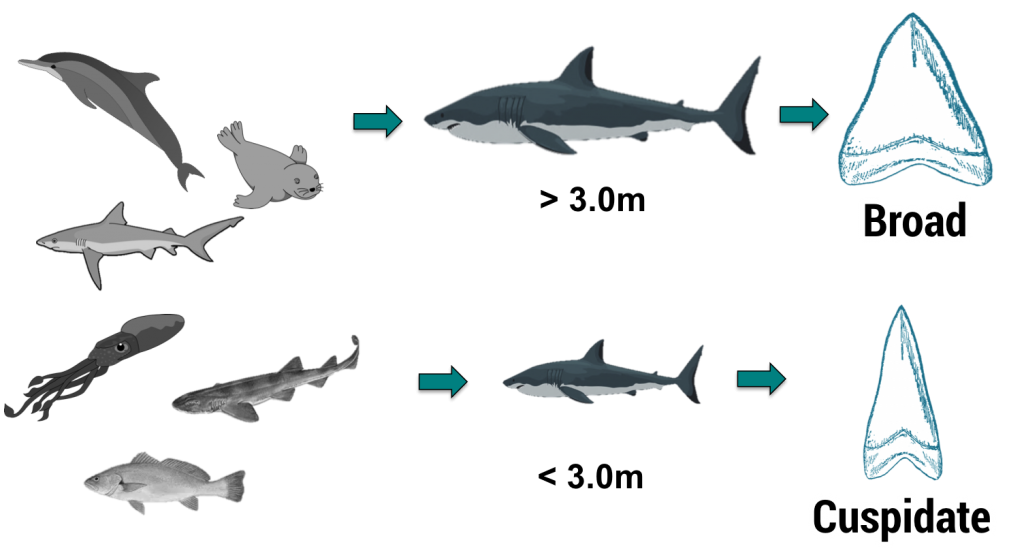

Up until now, scientists have accepted that white sharks start out their lives with cuspidate (pointy) teeth, which are thought to be adapted for gripping onto slippery fish. When the sharks hit roughly 3m in length, they’re then thought to develop much broader teeth, which are believed to be adapted for catching and eating marine mammals like seals and dolphins. This shift in diet and tooth shape with age/size is referred to an ontogenetic shift.

Accepted white shark food chain and concurrent perceived change in tooth shape

However!

When I started writing my proposal for my PhD on white sharks with the University of Sussex, I noticed a pattern of evidence in the published literature that suggested that this pointy to broad shift may not always be the case. Several scientists commented on either finding very large sharks with pointy teeth, or finding lots of variation in the pointedness of sharks of similar size. These comments were usually buried in studies that weren’t directly assessing tooth shape and/or the ontogenetic shift. They were also exclusively based on jaws from dead sharks. If I was going to study white shark tooth shape, I wanted to be able to get measurements from live sharks. But it’s not like you can politely ask a white shark to come over and open its mouth while you measure its teeth. Though that’s pretty much exactly what we did.

New non-lethal method for studying white shark tooth shape

The inspiration for this new method actually came from my time working for the Marine Conservation Society Seychelles (MCSS). My colleague Gareth Jeffreys published a paper on a photographic method to measure whale sharks with lasers (see laser blog for description of method). I adapted this to measuring shark teeth.

“But it’s not like you can politely ask a white shark to come over and open its mouth while you measure its teeth. Though that’s pretty much exactly what we did.”

Cage diving boats offer researchers and ecotourists the opportunity to get close up and personal with sharks on an almost daily basis. The majority of operators use a lure or decoy to encourage the sharks to come close to the cage. The act of the sharks trying to bite the lure/decoy generates a vast number of tourist and researcher photographs of the sharks with their mouths open – showing their teeth.

Say aaaaaaaah!

Myself and colleagues teamed up with the legendary Marine Dynamics, Dyer Island Conservation Trust, and volunteers with International Marine Volunteers in Gansbaai, South Africa to get high quality photos of the sharks displaying their teeth.

What did we measure?

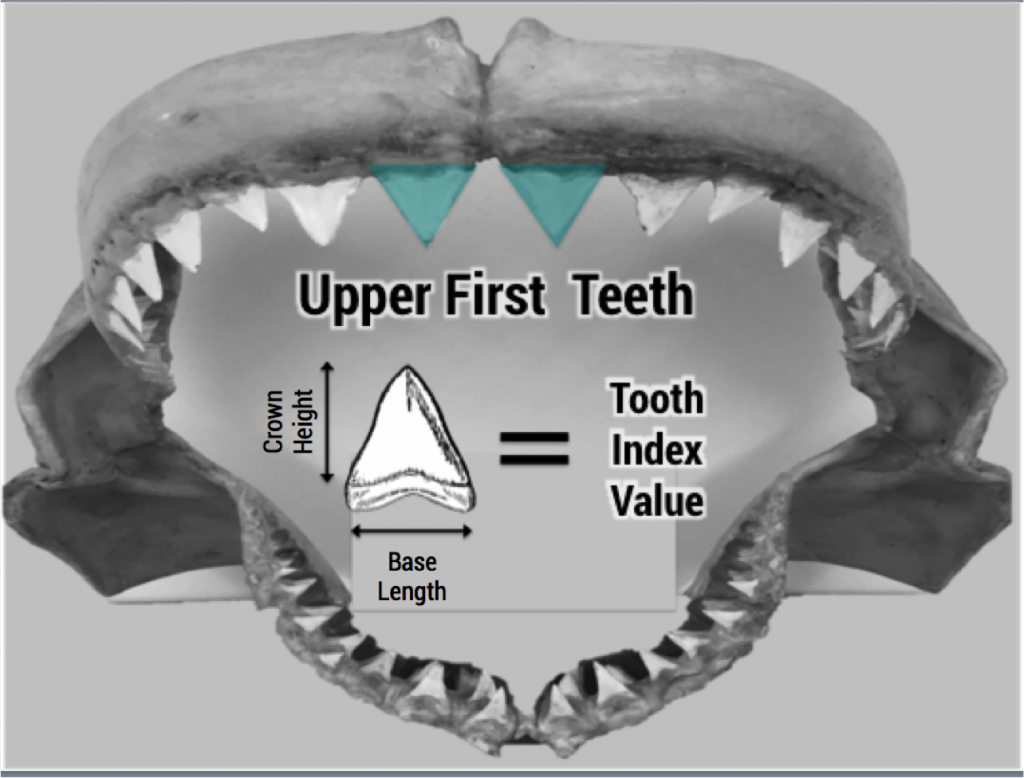

To calculate how “pointy” a tooth is, all you need to do is divide its height by its width. A high number indicates a pointy tooth, while a low number signifies a broad tooth.

Calculating tooth cuspidity/pointyness

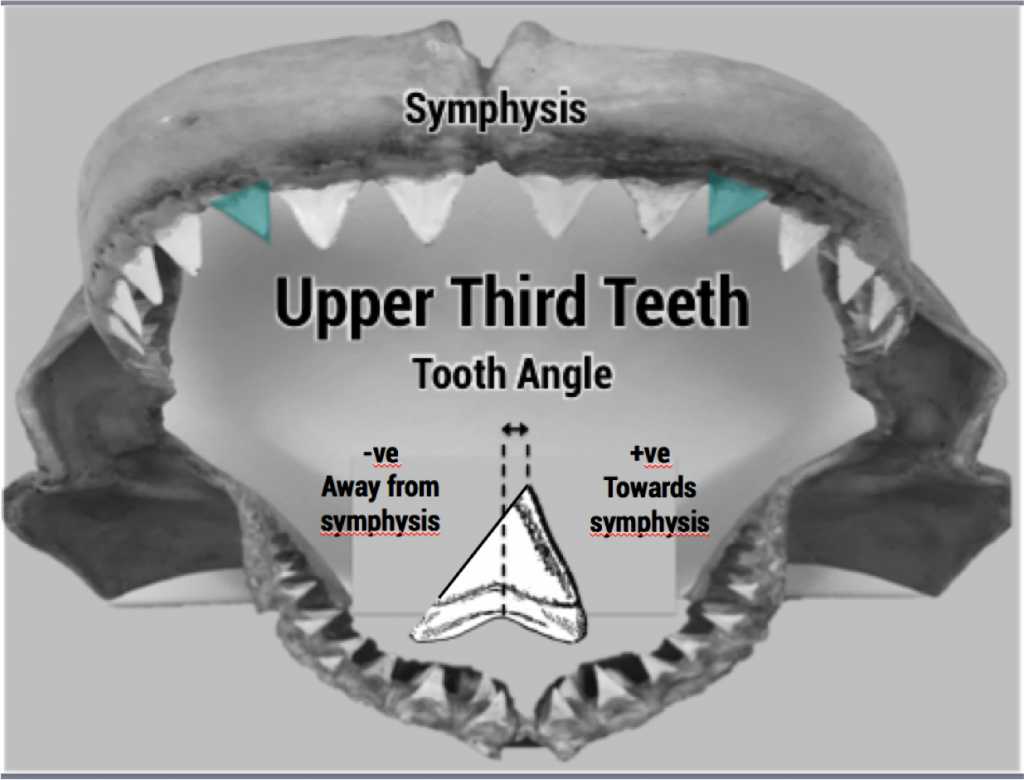

These “upper first” teeth were the easiest teeth to get photos of, and handily there was quite a bit of measurement data available for them in published literature (notably Hubbell 1996). There was also data available on the angle of the “upper third” tooth, which is thought to be specialised for inflicting large wounds on marine mammals.

Measuring the angle of the “upper third” tooth

I took tooth measurements in pixels using imagej software, eliminating the need for a ruler! We estimated shark length by comparing the sharks to the cage diving cage, which we knew was 4.7m long, and individually identified each shark using the unique outline of their dorsal fins and their natural markings. You can read about this here.

It was important that we test the method to make sure that it was both accurate and repeatable. For accuracy testing, we collaborated with the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board, who allowed us to use their jaw collection. We took photographs and direct measurements of the teeth, and when I compared the results of each method I was delighted to see that they were the same – the photographic method provides accurate data! From our photos of live sharks, I was also able to prove that measurements of teeth remain consistent across multiple photographs of the same individual, showing that the method is also repeatable.

What did the results show?

Previous studies of white shark teeth have always lumped males and females in together, despite the fact that they are quite different in other aspects of their biology and ecology. I decided to explore their tooth shape/shark length relationships separately. When I combined all of the data from the photographs, the literature and the KZN jaws, I found startling differences between the sexes. While males seem to follow the accepted pattern of broadening teeth when they get to about 3m long, females didn’t. Instead, a female of any size could have either broad, pointed or intermediately shaped teeth. Females also didn’t change the angle of their upper third teeth, while males did.

“When I combined all of the data from the photographs, the literature and the KZN jaws, I found startling differences between the sexes.”

What does this mean?

Broadly speaking, the results indicate that either males and females are feeding on different things as they grow up, or that the tooth shape change isn’t related to diet.

When sharks mate, males hold onto the females using their teeth. It’s possible that the broadening of the teeth and the change in tooth angle found in males could be an adaptation for mating, rather than for handling different prey. Alternatively, females with broad, pointy and intermediate teeth may be specialising on different types of prey i.e. they are polymorphic. I also found significant variation in the size at which males developed their broad teeth, which combined with other evidence indicates that some individuals mature a lot more quickly than others. Polymorphism and differing rates of maturity among individuals can have pretty big ecological consequences, and these factors need to be taken into account in future studies and white shark management.

This study further highlights how little we know about white shark biology and ecology, especially concerning differences between the sexes and individuals.

References

Hubbell, G (1996) Using Tooth Structure to Determine the Evolution History of the White Sharks. In: Klimley, A.P. & Ainley, D. (Eds.) Great White Sharks. The biology of Carcharodon carcharias: 9–18

Back to all News